Sacred Art and Frescoes in the First Christian Temples

|

|

Time to read 5 min

|

|

Time to read 5 min

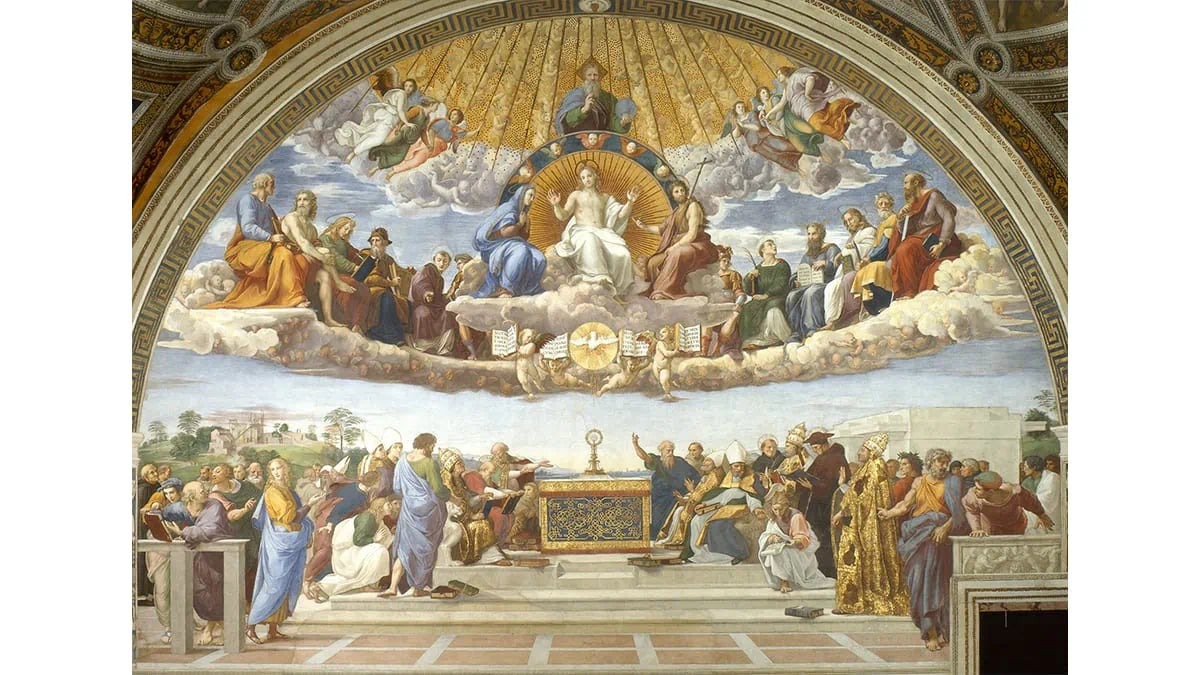

When the early Christian community emerged from persecution into public life in the fourth century, the Church found not only its voice in society but also its visual expression. With the legalization of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, Christians were finally able to build places of worship— the first Christian temples —where sacred space could be visibly shaped by faith. These buildings were soon filled with sacred art and frescoes , transforming architecture into theology and stone into storytelling.

The art of the early Christian temples was more than decoration. It was a visual proclamation of belief , a teaching tool for the faithful, and a means of transforming ordinary space into a glimpse of heaven. Drawing from Roman artistic traditions but infused with new spiritual meaning, early Christian frescoes and images turned the walls of churches into sacred narratives. This blog explores how sacred art and frescoes were used in the first Christian temples, examining their origins, themes, styles, and enduring theological impact.

Prior to Constantine’s Edict of Milan in AD 313, Christianity was largely practiced in secret. Worship took place in homes and catacombs , and early Christian art was limited to modest frescoes and symbols that adorned tombs and clandestine worship spaces. These included:

The Ichthys (fish) symbol

The anchor (hope)

The Good Shepherd

Scenes from Jonah, Daniel, and Noah—representing faith and salvation

With the legalization and imperial endorsement of Christianity, believers could now worship publicly and construct grander buildings . This marked the birth of the Christian basilica , and with it, the expansion of sacred art into the architectural domain.

The early churches, often called “temples” in Latin Christian texts, were modeled after Roman basilicas , which were originally civic buildings. Christians adapted this layout for worship, and in doing so, transformed it into a new kind of sacred space.

A long nave (central hall) where the faithful gathered

Side aisles for movement and processions

A triumphal arch leading into the apse , a semicircular area at the east end

The altar placed in or near the apse

A clerestory to bring in natural light

These spaces, with their high walls and large surfaces, became canvases for sacred art that could teach, inspire, and proclaim the faith.

In an age when most Christians were illiterate , sacred images served as visual theology —a way to convey biblical stories, Church teaching, and the glory of God through paint and plaster.

Didactic : Educating the faithful by illustrating scenes from Scripture and Christian tradition

Liturgical : Creating a fitting and beautiful environment for worship

Spiritual : Aiding meditation, devotion, and prayer

Symbolic : Using colors, gestures, and iconography to express complex theological truths

As Pope Gregory the Great later affirmed, “What writing presents to readers, a picture presents to the unlearned who look at it.”

A fresco is a painting made on freshly applied lime plaster, allowing the pigments to bond permanently with the wall. This method, common in Roman art, was adopted by Christians and used to decorate:

Walls of the nave and apse

Vaulted ceilings

Arches above doorways and apses

Chapels , baptisteries , and catacombs

Frescoes allowed large-scale storytelling across curved and expansive surfaces. Unlike later mosaics or icons, early Christian frescoes were often simpler, flatter, and more symbolic than naturalistic, emphasizing spiritual truths over physical realism .

The themes chosen for decoration reflected both the liturgical focus of the church and the theological priorities of early Christians.

One of the most iconic images in early Christian art is Christ Pantocrator (Greek for "Ruler of All"):

Depicted in the apse or central dome

Christ holds the Gospels and raises His hand in blessing

Often surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists (man, lion, ox, eagle)

This image affirmed the divine authority and cosmic kingship of Christ, especially important in a newly Christian empire.

Fresco cycles often included key events from Jesus’ life:

Nativity

Baptism

Miracles (e.g., healing the blind, raising Lazarus)

Crucifixion and Resurrection

Ascension

These narratives reminded worshippers of the mystery of salvation and connected the liturgy to the life of Christ.

Old Testament scenes were paired with New Testament events to show continuity and fulfillment. For example:

Jonah and the Whale → Resurrection

Moses striking the rock → Eucharist

Noah’s Ark → Baptism and salvation

This use of typology helped early Christians see the unity of God’s plan throughout Scripture.

Images of saints, especially martyrs , adorned the walls and pillars of early churches:

Represented with attributes (e.g., Peter with keys, Paul with scroll or sword)

Positioned in a way that surrounded the worshipping community

Functioned as spiritual witnesses and intercessors

This created a sense of “communion of saints” , uniting heaven and earth in worship.

Light played a significant role in early Christian sacred art:

Windows were positioned to illuminate key frescoes during specific times of day or liturgical seasons

Gold and white were used to reflect divine light and symbolize glory

Blue and red often denoted divinity and sacrifice

Color had symbolic meaning:

White = purity, resurrection

Red = blood, martyrdom

Green = eternal life

Gold = divinity and kingship

In this way, sacred art was not only visual but experiential , drawing the worshipper into the rhythms of light, space, and mystery.

The frescoes in early Christian temples shaped Christian imagination and belief in lasting ways:

Helped define orthodoxy , especially in the face of heresy

Reinforced the incarnational nature of Christianity—the belief that God became visible in Christ, and thus could be depicted in image

Created a visual liturgy that paralleled and enhanced the spoken Word and sacrament

Art became a means of revelation , not just reflection. It showed that theology could be not only heard but seen and touched.

Dating to the 6th century, this church preserves some of the oldest Christian frescoes in Rome, including:

Christ as Lawgiver

The Virgin Mary with Child

Saints in procession

One of the oldest known house churches (early 3rd century), featuring:

Baptismal frescoes of Christ and the Good Shepherd

A woman at the tomb—possibly Mary Magdalene

Depictions of healing and miracles

Early frescoes here include:

The Annunciation

The Madonna and Child

Women in prayer (possibly deaconesses)

These examples show how sacred art evolved from modest beginnings into a mature theological expression.

As Christian art developed, frescoes began to give way to mosaics in wealthier churches:

More durable and luminous

Created stunning apse and dome scenes

Preserved in churches like San Vitale in Ravenna

By the 6th and 7th centuries, icons —portable sacred images on wood—also became central, especially in Eastern Christianity. Yet frescoes remained important in smaller churches, monasteries, and chapels throughout the medieval period.

The frescoes and sacred art of the first Christian temples were visual proclamations of the Gospel —crafted with reverence, intention, and deep theological meaning. They turned ordinary stone into sacred narrative, surrounding the faithful with images of Christ, the saints, and salvation history .

For the early Church, art was not optional—it was essential . It was how they taught, how they prayed, and how they saw the world. In the frescoes of those first temples, the walls themselves became catechists, proclaiming in pigment and plaster the timeless message: Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.